|

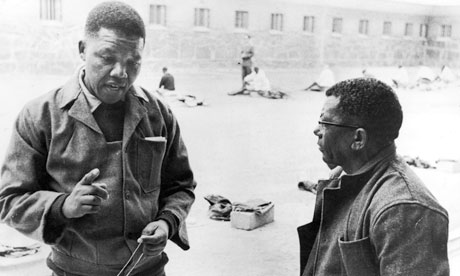

| Mandela on Robben Island Prison |

Sermon for Year A, Advent 2

By The Rev. Torey Lightcap

December 8, 2013

St. Thomas Episcopal Church

“Mandela”

Robben Island -- R-o-b-b-e-n Island -- is less than two square miles in total size.

It’s in an oval shape, basically flat, and it sits about six feet above sea level.

It’s a heap of stones with lime deposits on top --

Together, just a pile of minerals that have existed on earth, in one form or another,

For about a billion years.

Grass grows there sporadically, and a few trees.

In other words, as islands go, it isn’t much to look at: small, squat, rocky --

You can’t do a whole lot with something like that.

Robben Island is just a little over four miles away

From the warm, white sands of Bloubergstrand Beach,

A place known, among other things, for fantastic sunsets and good restaurants.

Bloubergstrand Beach is on the shore of Table Bay,

So called because of Table Mountain, with its wide, flat top.

And from the top of Table Mountain, at 3,500 feet,

You can see everything spilling out and below you in panorama:

Devil’s Head Peak, Signal Hill, Bloubergstrand Beach, and Robben Island out in the bay;

And on a clear day, the seemingly infinite reaches of Cape Town beyond,

The second most populous city in all South Africa --

Almost as far south as you can go on the entire continent before falling into the sea.

You can take in the whole of the northern half of Cape Town from the top of Table Mountain.

It extends north and then west, the knife’s edge of a waxing crescent moon.

The land almost reaches out for Robben Island, cupping it, then letting it go.

Turns out, that island was good for something.

It was a good place to put people you didn’t like -- specifically, prisoners --

Beginning in the 17th Century.

A good place to exile politically motivated men, potential rabble-rousers, movers and shakers,

From their homes and families (the list of prisoners is as long as your arm).

But not to remove them so far away that they could not see the shores of their homeland.

If you’ve ever taken the Alcatraz prison tour,

You can remember how close, yet how untouchable,

Are those big sprawling, teasing lights of San Francisco;

And you can imagine how torturous just that would be all on its own --

To toil and fritter and waste away in a cell on a nothing of an island,

And to do that for eighteen years,

When every day you could reach out your arm, spread your palm,

And imagine holding the cape in your hand.

Eighteen years was how long Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island.

From 1964 to 1982.

In South Africa, racial segregation was legally mandated.

It was called apartheid, which sounds a lot like aparthood, because it is.

Legislators after 1948 had created four racial groups: “white,” “black,” “coloured,” “Indian.”

You had to live in the places where your group was assigned

Or you could be forcibly removed.

Only whites were officially represented in government after 1970 --

Any other form of representation was abolished,

And so was non-white citizenship, and many spoke out against this, and many were broken.

Segregated were all the basic aspects of life -- almost any conceivable public service

Including medical care and education,

And you can bet that services for non-whites were vastly inferior, if they existed at all.

You can also imagine -- well, many political “undesirables,” and a place like Robben Island.

Mandela was but one John the Baptist on an island filled with John the Baptists,

Only where John chose the desert,

These men were forcibly exiled into their wilderness:

Leaders of student uprisings, freedom fighters, activists of all stripes,

And organizers of the African National Congress.

People trying, imperfectly, to gain access to basic human freedoms,

To point the way to something else, something better, something more.

Men charged with plotting insurrection, or conspiracy to commit sabotage.

Mandela had confessed in his trial to doing just that, and was convicted on those charges,

In addition to plotting to violently overthrow the government.

And so he spent his days on the island in backbreaking labor,

Splitting rocks and quarrying lime that was so white under the sun

It permanently damaged his vision. (The irony of color.)

At night, he tossed on a straw mat in a damp 8’x7’ concrete cell.

Without a doubt, wilderness experiences shape a person,

But equally doubtless is that who a person is, or is willing to be,

Also shapes the experience for others.

During the trial that eventually sent him to Robben Island,

For the first eighteen of his twenty-seven years in prison,

Mandela learned that a courtroom can be a bully pulpit.

Now he would learn that a prison can become a university,

A testing ground for new ideas,

A place to cautiously raise complaint in the face of daily and systemic abuse,

A place to very slowly change things for the better.

For the first eleven years of what was then a life-sentence,

He was allowed one visit and one heavily-censored letter every six months.

When his mother and his son died, each in the late 1960s, he remained in restraint on the island,

Forbidden from attending their funerals.

Now, of course, a week from today we will have the funeral of Nelson Mandela

In the small rural village of Qunu, his home in eastern South Africa.

And there will be no restraint. It will be one of the biggest state funerals ever.

Many thousands will come to celebrate and to mourn, to sing and to pray

In thanksgiving for the life of one human being

Who had a chance to leave things in his world better than he found them;

Who, imperfectly, over time, picked his way

To a path where he found himself leading.

He will not be eulogized primarily as the prisoner he was,

But rather as the eventual President of South Africa he would become after leaving prison;

As one who helped dismantle apartheid,

As one who led the way on a long walk to the reconciliation of a nation

Still at war with itself even after the end of apartheid.

A reconciliation he defined as “working together to correct the legacy of past injustice.”

But there will always be someone who cannot come to pay his respects

Because he is chained to a wall.

Perhaps some of our more blantantly sinful institutions have been taken apart,

But more remains to be done than we can measure.

Our weapons in the fight are the courage and the awareness of the prophets,

Who pour bitterly cold water on our sleepy eyes whenever we want to pretend everything’s okay.

These prophets -- they rarely come to us in a way that makes us want to greet them with joy.

They point out our most basic faults with precision.

They seem to us so wild; their tongues are untamed; their critiques cannot be shackled.

They push at our dearly-held boundaries, wanting us to see what lies beyond them;

They tell us to watch out, to change our ways and repent;

They foam and rage, that it is well past time to amend our laws, our lives and hearts;

They say -- well, they say all kinds of inconvenient things.

Truth is, we don’t know what to do with them, so we gather them in and lock them away,

Believing in the lie that the truth can be surpressed so far down

That it can cease to be relevant.

We find it easier to heap blame on these prophets than to listen to them.

We let them rot in jail like Mandela, thinking we can drain away their spirits --

Or in John’s case, we let the egos of leaders decide their fate

In moments of utter injustice.

In his first letter to the new little church at Corinth,

Paul wrote that “God chose what is nonsense in the world to make the wise feel ashamed.

God chose what is weak in the world to make the strong feel ashamed.”

“Feel ashamed.” In other translations, “to shame the strong and wise.” In others, to confound them.

It is the Lord’s gracious prerogative to raise up the prophets and the tellers of truth,

And to see them through whole generations of hard labor,

That one day, when they can be heard, they might find within themselves the gall

To demand that we come to our senses, and the world be stunned enough to listen.

They do not prophesy in order to be liked;

They come, instead, to tell us how it is, and how it will be if we hold trajectory without turning.

And they offer us an opening, an alternative -- another way to go

To preserve life, build up society, reorient that which is unjust,

And point toward God, that others may stream to the great light of the Kingdom of Heaven.

The danger is in imagining that these special tasks are only for a very few

Who have some sort of divine appointment.

I tell you, in Jesus’ name, NO.

Each and every person who is baptized is called to tell the truth --

To point out where we need to change, no matter how uncomfortable or unpopular it makes us.

As Mandela wrote in his autobiography,

“Man’s goodness is a flame that can be hidden but never extinguished.”

The prophetic potential lies within us all, waiting to be brought forth.

The world needs it:

And what, really, is the discomfort of a Robben Island, of all our Robben Islands,

When we already know we have had this call placed upon us?

God needs people willing to risk it all for the sake of the betterment of this world.

No comments:

Post a Comment